It is helpful to use other phrases for people who have in the past been described as “mentally ill.” This is a living essay, and the author updates it periodically. If you have any feedback or suggestions let the author know c/o the MindFreedom office. [Modified 8/28/12.]

Let’s Find Language More Inclusive Than the Phrase “Mentally Ill”!

by David Oaks, Director, MindFreedom International

- How can we be more inclusive with ourlanguage in the mental health field?

- How can we show those who havebeen marginalized by psychiatric labels that we are listening andwelcoming?

This essay is not about being “politically correct.” What is “correct” changes with the winds and tides and individual.

This is a call to stop the use of the term “mentally ill” or “mental illness” and find replacements!

Here are some suggested alternatives:

- Psychiatric survivor

- Mental health consumer

- User of mental health services

- Person labeled with a psychiatric disability

- Person labeled with psychosocial disability

- Person with a psychosocial disability

- Person diagnosed with a mental disorder

- Person diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder

- Person with a mental health history

- Person with mental and emotional challenge(s)

- Person with a psychiatric history

- Psychiatrically-diagnosed

- Person with mental health issues

- Consumer/Survivor/eX-inmate (CSX)

- Mental health client

- Mental health peer

- Person who has experienced the mental health system

- Person with psychiatric vulnerabilities

- Person with lived experience of mental health care

- Person who identifies as a survivor of psychiatric atrocities

- Psychiatrized

- Neurodiverse

- Upset

- Distressed

- In crisis

- In despair

- In ecstasy

- Different

- Overwhelmed

- Extremely overwhelmed

- Person in mental health care who is on the sharp end of the needle

- Survivor of forced psychiatry

- Person with lived experience of the extremes of the human experience

- Person who experiences problems in living

- Person experiencing severe and overwhelming mental and emotional problems [describe, such as “despair”]

- Person our society considers to have very different and unusual behavior [describe, such as “not sleeping”]

- I have a name, not a label! Insert Your Name Here [e.g. Jane Smith]

- Person.

- Citizen.

- Human being! Period!

- Etc.? Your creativity is welcome, add to this list!

This Essay is Not About Perfection!

These suggestions about language are not about finger-wagging or shaming anyone into “perfection”! Too much of our society is too harsh already!

I love word origins, and the root meaning of the word “perfect” is “finished.” Are we ever really finished with a living language?

In fact, can we ever perfectly describe reality, at all?

No!

The term “mentally ill” is very much a narrow medical model.

If you want to use that term about yourself that is one thing. But when anyone uses the phrase “mentally ill” about others, including me and other psychiatric survivors, the implication is that since an “illness” is the problem then a doctor ought to be part of the solution. “Mental illness” also says since the problem is like a materialistic physical illness, then perhaps the solution ought to be physical too, such as a chemical or drug or electricity.

Please note a subtlety here:

My call is not about opposing the medical model, or any other particular model.

My call is about opposing domination by any model in this complex field. My call is about opposing bullying in mental health care.

So let’s also drop the use of other words that tend to confine us in the dominant model. Let’s stop legitimating the use of words and phrases like “patient” and “chemical imbalance” and “biologically-based” and “symptom” and “brain disease” and “relapse” and all the rest of the medical terminology when we are speaking about those of us who have been labeled with a psychiatric disability.

By the way, have you been noticing a few “quotation marks”?

Since 1969 when the movement began, mad activists have questioned language. What some activists do to provide just a little bit of breathing room between us and mental health industry language, is the generous use of quotation marks.

For example, for decades some in our movement have changed this:

People with schizophrenia.

to this:

People with “schizophrenia.”

Quotation marks like this help the activist writer a bit, to show that it’s not the writer’s word, that he or she is just quoting someone else. But we want more than punctuation. Punctuation can disappear, such as when it is read aloud. Too many quote marks can also get a bit annoying, too, because after all shouldn’t the above be:

People “with” “schizophrenia.”

Because who is it who is claiming I “have” some illness, anyway? Relying on quote marks alone can make your text look a little strange!

So go ahead and use a few quote marks, but even better would be to change the wording itself, such as changing the above to:

People diagnosed with “schizophrenia.”

or even better

People labeled with “schizophrenia.”

The reason for that final suggestion, is that I’ve known activists such as Rae Unzicker who don’t even want to give legitimacy to this process by using the word diagnosis, a word which mean identifying an illness based on science and medicine. This is a bit of a fine point, so I tend to use diagnosis or label interchangeably, unless it’s about an individual who personally identifies himself or herself with a particular diagnosis.

Yes, this essay has gotten a little long for the Internet, but exploring the complexities of language – even if it takes a few extra words – is far better than just tagging people with a judgmental and harmful label!

History of Psychiatric Labeling: Do Not Brand Us.

While psychiatric institutions have been around for centuries, it’s really in the 1800’s that the huge institutions began.

A feminist anthropologist historian Ann Goldberg has looked into the real life stories of those who were locked up in an early big institution in the 1800’s, in Germany, in her provocatively-titled book Sex, Religion and the Making of Modern Madness. Essentially, her research seems to show we have been some of the people who have not “fit in” to a modernizing society, a society that has some major problems itself.

The emergence of the medical model as psychiatry’s dominant ideology has a fascinating history, such as in the 1800’s in England when “mad doctor” elites jostled with one another to create the early journals, regulations, associations, licensing, government funding and large institutions. The medical model was simply a kind of rallying flag to consolidate the power of the dominant psychiatrists.

The emerging medical model of the 1800’s was about setting boundaries for power, and it was not about science. After all, the main “medical model” during the rise of that ideology was phrenology, the study of bumps on the head, which even then was beginning to be discredited.

I highly recommend the superbly-researched book Masters of Bedlam by historian Andrew Scull et al. to understand how a few hundred elites in England in the 1800’s helped construct the medical model domination system we see today. Scull points out that one of the first, most influential books promoting a medical model of mental health in the 1800’s barely even mentioned that ‘flavor of the day,’ phrenology, which the author finally added as an afterthought in his dedication.

Ironically, today, psychiatry’s own official label bible, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, does not refer to the phrase “mental illnesses,” but to mental disorders. Even inside the DSM, which psychiatry generally believes albeit falsely to be scientific, they do not use the phrase “mentally ill” in diagnosing, so it is actually scientifically impossible, by psychiatry’s own standards, to be officially “diagnosed mentally ill.”

In May 2012, MindFreedom led a peaceful protest of 200 marching in front of the American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting in Philadelphia, protesting the DSM and even ripping up our labels. You can see photos and videos here.

Words Matter, Especially When They Have the Force of Law.

Psychiatric diagnosis has a tremendous amount of undue power.

I was diagnosed schizophrenic and bipolar, and found myself under the catch-all label of psychosis. To admit one has been officially labeled psychotic is perhaps one of the deepest closets to come out of, because the discrimination against those with that “p-word” label is so immense.

I prefer to talk about “discrimination,” rather than “stigma,” because discrimination is something we can actually challenge and change, such as through legislation. The word stigma, of course, comes from “branded,” and implies that my identity as a psychiatrically-labeled person is inherently negative, which is not always the case.

I would rather ask, “Who is doing the branding?”

The pseudo-scientific aura around the composition and organization of the DSM is reminiscent of the book once used to “diagnose” witches, the infamous Malleus Maleficarum (Latin for “The Hammer of Witches”, or “Hexenhammer” in German).

Today, who benefits by seeing extreme or even mild mental and emotional problems as primarily a “biologically-based” issue? Those who primarily promote a narrow medical model approach — such as the pharmaceutical companies — benefit by a medical model language.

Certainly, in the long run, taking away the unfair legal power that a few hundred psychiatrists have in literally voting on what courts and legislatures consider “normal” is an important goal. USA psychiatrists are currently working behind closed doors on their fifth revision of the DSM, which has international implications. For years, despite our many requests, the organizers of early meetings on these revisions, such as the influential USA psychiatrist Dr. Darrell Regier, refused to open those doors, or to even respond to civil inquiries.

Illustrating the complexity of language, the APA has found itself terribly divided internally about this next edition, and therefore they’ve delayed publication at least a year, to 2013. The main editor of DSM-IV, Allen Frances, has denounced the APA’s work on DSM V. After public pressure, including by MFI, the APA opened up a bit, and has created a DSM 5 web site to gather public comments about its draft.

We want far more than input on a web site to the few hundred privileged professionals who literally vote on our labels.

In the long run, we must stop all “Psychiatrization Without Representation.”

In the short term, we can at least try to change the language we personally choose to use. I know many of my friends in our mad movement — including psychiatric survivors, dissident mental health professionals and authors — freely use the term “mentally ill,” because they think it’s more recognizable by the public. However, in the field of Intellectual disabilities, many groups now have campaigns to get rid of the frequently-used “R word.” And of course civil rights activists have largely effectively fought the “N word.” Frequency of word usage does not eliminate the pain that is caused, and does not make change hopeless.

This Call is About Valuing Inclusion, Diversity, Respect and Empowerment!

I understand that many people define themselves as “mentally ill,” and accept a medical model. If you do this, that is your choice. I respect you.

However, at this time, the “medical model” is dominant. The medical model has become a bully in the room. Language that somehow encourages that domination isn’t helpful to the nonviolent revolution in the mental health system we need, a nonviolent revolution of choice, empowerment, self-determination.

What about the many other people who define their problems from a social, psychological, spiritual or other point of view? And what about those who don’t see their differences as problems, just as differences, or even as qualities?

In fact, what about the subject of defamation? According to an attorney we work with, to falsely claim an individual is officially “mentally ill” with intent to harm them has been used in law schools as a classic example of defamation.

We’ve come up with some of the suggested alternatives listed at the start of this essay, using good old-fashioned plain English. Each phrase and word has difficulties of its own. There are many creative ways to address this. Perhaps you have some suggestions yourself, let us know.

I’ve heard that some feel that using alternatives to medical model language somehow diminishes the seriousness of people’s personal pain, that, for example, being diagnosed with “clinical depression” underlines the gravitas of a crisis better than, say, “sad.” But there are words in the English language more fierce than “sad.” How about, for example, “extreme and catastrophic life-threatening anguish”? That phrase has a lot more gravitas than any clinical language I’ve ever heard! (The origin of the word “clinical” by the way, is simply related to “bed.”)

So speaking of everyday English, what about slang words for us? As with any oppressed minorities, these words can hurt, and sometimes the words are meant to hurt.

After all, English is a living language that changes. Back when psychiatrist Loren Mosher created a model alternatives, “Soteria House,” the idea of a peer was just about anyone who did not have mental health training. In other words, a caring member of the general public was considered a “peer.” But more and more, we are hearing the term “peer” somehow become used as shorthand for “person who has used officially licensed mental health services.”

Some activists, including me, at certain times have sought to reclaim the words society has thrown our way. I realize others may not choose to ever use words like “mad” or “lunatic” or “crazy” or “bonkers” to describe themselves. We probably ought not use those colloquial terms in certain contexts, like arguing our rights in front of the United Nations or in a court hearing. But now and again, some of us like to have some fun and be outrageous, such as at MAD PRIDE events, where it is okay to be creative and reclaim language that has been used against us.

We even have a parade entry with the sign, “Crazy = Normal, Normal = Crazy.”

But this is us laughing with us, and with all of society, to further our goals. That’s different than someone exploiting us for their own private goals.

Speaking of laughter… Consider the stereotyped ‘crazy evil laugh’ one may see in a movie with, say, a mad doctor. You know, that “moo – hoo – hoo – hoo – ha – ha – ha!” laugh. Why is that considered inherently mad? Isn’t that sometimes the sound an extremely disenfranchised person makes who has suddenly discovered the tables have turned, and he or she is winning because of a cunning plan? Is that victory laugh really always evil?

In the right context, I love to recapture some of the words used about us. We do, after all, get a lot of the fun animals such as squirrely, crazy like a fox, bats in the belfry and loon.

When we have a mad potluck, I have been known to bring nuts, bananas and crackers in a cracked pot. Here at the MindFreedom office we have two whistles that make the sound of a loon, and a loon stuffed animal! I have hesitated at getting a cuckoo clock, since one never knows who might be on the phone when the clock strikes twelve.

When we gave an award to clown/physician Patch Adams on July 14, 2012 for his leadership in the IAACM, he asked that it not focus on his being a ‘psychiatric survivor,’ but for his proud ‘lunacy promotion.’

Madness and Change

I love it that the word origin of “mad” is essentially change, similar to the two letters “mo” in “motion” or “emotion.” You bet some of us want change, and often change is considered “mad.” Perhaps you’ve heard someone whisper about a mutual friend going through emotional turmoil, “She’s… changed…. she’s just not the same person.”

Questioning our language can lead to fascinating discussions about words related to madness.

For instance, the three words “stark raving mad” create one of the ultimate and undeniable descriptors of an individual considered psychotic. Word origins could translate that phrase into “staring intensely in extremely hungry rapid movement.” In other words, this state is similar to that intensely focused look a wild predatory animal like a wolf has in the final microsecond before landing on its rabbit lunch.

It’s revealing that our society has described that particular “extreme assertiveness,” which can be as natural as any scene in a documentary about lions, or any scene from Homer’s Iliad, as inherently always a sickness. In fact, couldn’t those words ‘staring in hungry pursuit’ sum up the ethic of our current consumer society? Have you ever reflected at just how ‘driven’ a driver on our crowded roads looks, hands held on the wheel in a kind of prayer? The drone of thousands of tires on highway seem to say one word to my imagination: “More… more… more….”

Once more we can glimpse that society does not always oppose a particular ‘altered state’; society may seek to monopolize the power of that altered state only for is own exclusive, so-called ‘normal’ purpose. Sanctioned “stark raving madness” for economic gain, to win a football game, or for an official military operation, have all become so widespread it is considered normal. When unsanctioned, those who tap into this particular state for good or for ill can be considered inherently out of bounds. Not all “stark raving madness” is good, but I know that breaking with what is called “normal” for the greater good may at times look like “stark raving madness.”

Moments of extreme assertiveness do not have to be inherently violent and destructive. MindFreedom has a policy of nonviolent action, but nonviolence can certainly include extreme assertiveness. Martin Luther King and Mahatma Gandhi often said that civil disobedience was not a form of passivity, but of soul force or satyagraha.

Rosa Parks, sitting on a bus in the segregated south and refusing to give up her seat, was not ‘passive.’ Her calm dignity that day was in fact ‘staring in hungry pursuit’ of justice, connected to a powerful movement.

Any discussion of the language of madness needs to include a mention of how Martin Luther King, Jr., in over ten of his speeches and essays, said he was proud to be psychologically “maladjusted.” It is highly recommended that everyone who cares about change in the mental health system become familiar with Martin Luther King’s use of this term “maladjusted.” For at least a decade, he said in a variety of ways, “Human salvation lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted.” In fact, he even repeatedly said the world was in dire need of a new organization, the “International Association for the Advancement of Creative Maladjustment” (IAACM).

Take Back Mad Words!

I feel words such as “crazy” can actually be positive in certain contexts. Consider, “I’m crazy in love.” Isn’t the only real love, crazy love? Recall Apple’s early motto for their computers, “Insanely great.” The word origin for crazy is “cracked,” and in Japanese art the pottery with a beautiful imperfection has a special Wabi-Sabi value.

The problem with this kind of language begins when it becomes mainly attached to negativity. A newspaper editorial or journalist disparaging certain citizens as “lunatics” ought to be opposed.

To this day, when I give public speaking engageements, I ask people if they have heard of racism or sexism or classism or ablism. Obviously, most everyone has, and nearly all hands shoot up. But then I ask if anyone has heard of sanism, and few people have. Even some long-time activists in mental health say they’ve never heard of the word.

Our’s literally is an oppression that shall not be named!

(By the way, I know some good friends have used an equivalent term “mentalism.” However, it turns out mentalism is also a school of philosophy, as well as a type of magic. Attorney and professor Michael Perlin has championed the use of “sanism” instead.)

Whatever you call an oppression, the phenomenon of “Isms” is often caused by exaggerating real or imagined differences to such an extent that instead of celebrating diversity one creates an irrational chasm. To this day I am still exploring the depths of the chasm of “sanism.” and I have still not found its bottom.

And shouldn’t we expect “sanism” to be especially deep?

Humans differ by gender, age, racial heritage and religion. These differences, when distorted, have led to discrimination. But how do human beings tend to define themselves? When a typical person is asked to describe the difference between themselves and non-human animals, I can imagine he or she would say, “Humans are the rational animal. The thinking animal. The animal that can do math, fly a plane, engage in commerce.”

Since we humans typically define ourselves by our minds, then those who are considered fundamentally different in their minds can encounter a type of discrimination that is on a profoundly different level than other “isms.”

When major global organizations such as World Bank and World Health Organization have needed to study the impact of mental and emotional problems on society, they often use a measure that is called “days out of role.” This method of measurement may work fairly well for, say, automobile accidents. One can come up with a number of days people harmed by automobile accidents are not fulfilling their chosen role of worker, parent, student, etc., and then give that a monetary value. However, as we now know, mental and emotional differences and difficulties are far more complex than a car accident. It is revealing that the ultimate definition of a mental and emotional problem by these international bodies is when you are not fulfilling your “role” in the great system of commerce that is a dominant force in the world today.

Once more, we can learn a bit from word origins. The word origin for “role,” it is thought, came from the fact that actors in the 1600’s were handed a “roll” of paper with their script for being a character a play. In other words, one’s “role” is the part played by a person in life, as one dictionary puts it. Again, this may work for something as simple as measuring the impact of car accidents. But when it comes to measuring mental and emotional well being, shouldn’t we have a measure of the number of days in one’s life that one fulfills the role one has written for one’s self? How many days are we living the life of our dreams?

Is “Mental Health” Bias Lessening?

Sometimes I’m told that things are getting better, because so many people are “labeled.” There are celebrities and co-workers who candidly discuss their diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or attention deficit disorder. However, in some ways things are worse for one of the most serious diagnoses, “psychosis.” As I’ve noted, technically “psychosis” can include many of the people who are labeled schizophrenic and bipolar.

So you know those many young people being diagnosed “bipolar”? Well, they may want to know that many of them are also being diagnosed “psychotic,” a particularly-offensive label that can stick to them for life.

Imagine moving into a new house, and your neighbors discover you have a diagnosis of “psychotic.” You will probably discover that this label still carries a lot of power.

Ironically, though, the word origin of psychotic is simply “soul sickness.” And is there anyone who doubts that our society today has one heck of a lot of soul sickness?

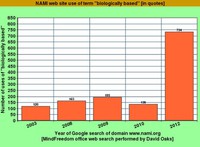

One indication that the “medical model” approach is holding on is a simple and informal test. For nearly a decade, MindFreedom has done a Google search of the web site for NAMI, the National Alliance on Mental Illness, for their use of the phrase “biologically based” (in quotes).

While this is an unscientific study, I’m alarmed that in 2012, the number of references – reflected in the bar graph here – has skyrocketed four-fold from just two years ago.

Care to Go Deeper? Climate Crisis, Quantum Theory & More

If I may get a little “big picture” here, in the modern scientific field of “complexity theory” (also known as emergence theory, chaos theory, systems dynamics, etc.) life and the mind appear to be a phenomenon emerging from the edge between chaos and order, far from equilibrium. That is, our mind – and life itself – literally ‘plays itself out’ on the edge between chaos and order. What appears to be “stability” is often a dance on this edge.

I highly recommend the little book by Fritjof Capra called Web of Life for an elegant description of this enormous scientific revolution, that is replacing the old Newtonian view that life can be reduced to parts of a machine.

For me personally, the environmental movement has helped our “mad movement” a great deal. That is because in recent decades, environmental scientists have produced convincing evidence that what is called “normal” behavior in our society is leading to the destruction of our planetary ecosystem, and an untold number of species. In other words, the similarities between so-called “normal” people and so-called “mad” people may be far greater than the differences.

Of course, a teenager threatening suicide, for example, is in a terrible crisis and we as a society must provide humane, compassionate, and wise assistance on an urgent basis. However, we also need to remember that all of humanity — in its self-destructive adolescence — is far more similar to that suicidal teen than they are different. Sometimes realizing our commonalities can play a big role in providing empathy. In a way, one can see the label as “crazy,” as essentially saying that someone else’s behavior or thoughts are simply so non-understandable, so non-predictable, that they are beyond the realm of your imagining why they might do this.

A classic example is a person running screaming naked down the middle of the street. For many people that’s a very good example of “crazy.” That is, until they listen more closely and discover that this is a mother who is screaming about her burning home, and that her child is trapped inside.

As attorney Susan Stefan put it in a keynote address to the National Association for Rights Protection and Advocacy, perhaps our best response to the over-simplicity of the “chemical imbalance” theory of the mind is to respond, “We are more complex than that!” The psychiatric survivor movement has a special role to play, because there is no evidence of any “chemical imbalance” or physical difference.

Throughout the sciences, theories involving quantum theory, string theory, particle physics and more, are discovering that existence is far weirder than scientists ever imagined, and that no one truly has an absolute grip on reality. We apparently all need one another’s hearts and minds, together, to make even our best guess about ‘what is real’ – and even then, we know we are only making our best collective guess.

Lessons from Cross-Disability

All of these issues also apply even when there are significant and proven physical differences, such as for people who have experienced major brain trauma, such as from strokes or car accidents. Those who have sought recovery point out that over-labeling and over-medicalizing can often hurt their empowerment, which is a key value for true long-term recovery.

Many deep thinkers in the broader cross-disability movement, that includes people diagnosed with visible ‘physical’ disabilities, also wrestle with many of the same language questions raised here. In fact the prefix, “dis,” inherently is itself a negative. Some clever disabled folk are calling themselves “The Dis-Labeled.”

Famously, many people with hearing “differences” say they are not disabled, that because of their alternative-language skills they are their own special culture.

Many senior citizens resent being called disabled, even if they have a walker and a hearing aid, and prefer the term ‘senior citizen.’

And what of those missing legs – such as Iraq veteran and athlete Noah Galloway – who have newer prostheses that allow them to run faster than many so-called “normal” person, such as ? In a flat-out race, who is now the “disabled”? There are many books and films on the rich topic of normality and disability in general.

One of the most revealing books on ‘normal’ is actually from the environmental movement. Tenured University of Oregon professor Kari Norgaard has studied a prosperous, well-educated town in Norway for a year, about why these ‘normal’ people, who seem fully aware of the climate crisis, are doing very little to address it. As I said above, is it truly ‘normal’ to be numb to one of the main issues of our day?

The point is we are not going to find perfect or correct or language.

Our “mad” social change movement has wrestled with language for decades, and there is no consensus. There may never be. This fascinating, frustrating, ongoing discussion is in fact the solution.

Diverse speculation is a wonderful antidote to the falsehood of certainty.

So, We Can at Least All Show We Are Trying!

The immensity of psychiatric industry oppression is so great, on so many levels including physical, emotional and even spiritual, that it can often be overwhelming. That is how even subtle psychiatric oppression tends to mute those who are impacted. Or another response to that oppression when it rises to torture may in fact be a scream, as psychologist and psychiatric survivor Ron Bassman has movingly explained in his book, “A Fight to Be.”

However, most of us can still control our tongues, our fingers, our language, our writing… and our minds. An ancient peasant rebellion song, Die Gedanken Sind Frei, celebrates the undeniable fact that “thoughts are free” and could serve as our anthem.

An oppressed group often seeks to redefine themselves as a first step toward liberation. For instance, many leaders of people we have known as Gypsies are asking to be called Romani. Look at all the permutations of language for African Americans just in the past century.

Mental health academics, such as Linda Morrison, PhD with her dissertation-based book Talking Back to Psychiatry, have even written treatises exploring the history of our movement’s ongoing wrestling match with language.

Why bother to replace “mentally ill” with something else, with anything else?

- We can show we are at the very least trying to listen to psychiatric survivors (like me!) who have strong preferences for what we call them.

- We can show we are trying to include a wide diversity of perspectives, including those who have often been excluded because of the current dominant paradigm in mental health.

- We can show we are trying to care, and that we too seek a nonviolent revolution in the mental health system!

If you need one more reason to stop saying “mental illness,” observe that sometimes our opponents can inform us about what may be an effective strategy. In 2010, the annual federally-funded Alternatives Conference that gathers up to 1,000 mental health consumers and psychiatric together to discuss peer-run projects, was politically attacked afterwards primarily because organizers dropped the term “mentally ill” from their program and publicity materials.

So please, become a pioneer, and together let’s drop the use of the phrase “mental illness,” and search for more inclusive and creative phrases. This is a reminder that our words and even our whole social reality of what is called “normal,” are not forced upon us God-given by the heavens, but are constructs that we mortals all co-create, in our imperfection, in our freedom, together.

Feedback on this essay is welcome: news (at) mindfreedom (dot) org

Share this essay! The web address is:

http://bit.ly/not-mentally-ill

or

Document Actions